bog, \ˈbäg, ˈbȯg\, noun, wet spongy ground; especially: a poorly drained usually acid area rich in accumulated plant material, frequently surrounding a body of open water, and having a characteristic flora (as of sedges, heaths, and sphagnum) —Merriam Webster Dictionary

How dreary to be somebody! How public like a frog To tell one’s name the livelong day To an admiring bog! —Emily Dickinson

In 1982, a man operating a tractor on the central east coast of Florida raised the wide steel bucket of his digger and brought up a scoopful of human heads. Estimated after radiocarbon testing to be over seven thousand years old—predating by millennia both Stonehenge and the Egyptian pyramids—the skeletal remains discovered in the sludgy quagmire of what’s now known as the Windover Archaeological Site (or Brevard County Bog), were remarkably well preserved by the earth’s curative acids, transformed into dark artifacts of an eerie, oily beauty.

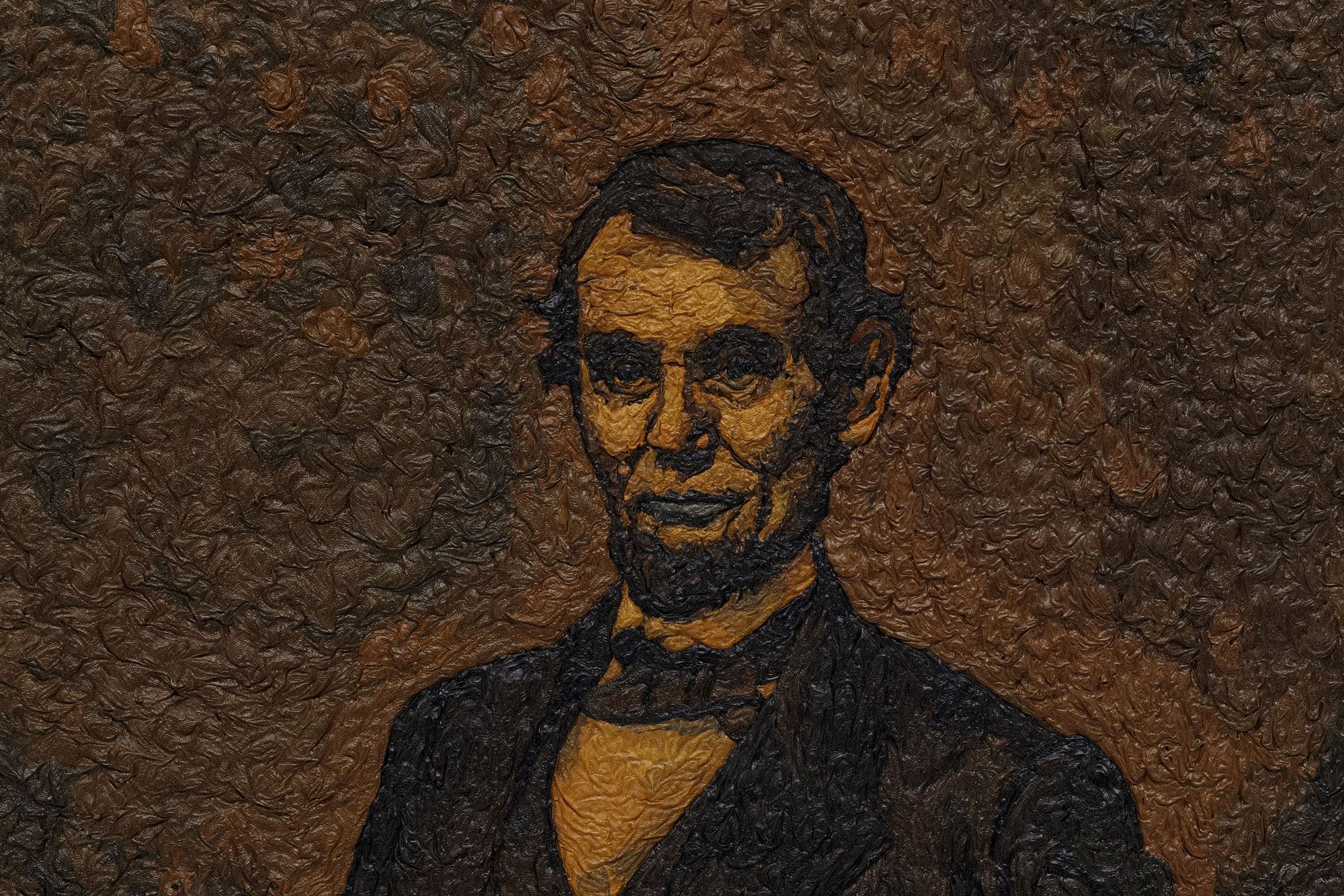

American Bog, Mark Alexander’s new exhibition is motivated by the creative profundities of such happenstance ancient excavation. In nine new works, the British-born artist’s brush approximates the swing and jut of the paleontologist’s pick and chisel, as though he were bringing to light after an amnesia of centuries, the turf-fermented fibres and soil-crumpled countenances of iconic Americana. From the Stars and Stripes to a portrait of Abraham Lincoln, from Mickey Mouse to JFK, the artist unpicks the porous psyche of a superpower as if from an intimate, though inconceivably distant, future perspective. The result is a salvaging of symbols that have been buried under the weight of too much staring, a revivifying of overly-familiar signs by replacing their tired tissues with the fresh flesh of unfathomable age. As if marinated for centuries inside Alexander’s bog, the shapes of culture collected here share an alien appearance—a tenderly toughened complexion that challenges conventional aesthetic notions of what constitutes artistic beauty.

The American bog in Windover Florida, which converts all that is buried there from fragile dermis to enduring objet, secretly churns between locations that loom more glitteringly in popular and patriotic imagination: Disney World, sixty miles west, and the Kennedy Space Center (near the launch pads of Cape Canaveral), twenty-five miles southeast. Such proximities are telling. The creative chemical forces at work deep inside the bog’s mysterious recess, measuring time in excruciating geological slowness, comprise a soulful rejoinder to the impatience and ephemerality of contemporary cartoonish celebrity on the one hand, and the passing geopolitical grudges of space-race mentality on the other. These tensions percolate darkly too beneath the tarred surface of Alexander’s strange, stark, unsettling paintings and can be fathomed in the tortured texture of everything his easel his brush and easel have disinterred.

American Bog marks the second phase of an ongoing artistic project that began in autumn 2012 with the launch in London of Mark Alexander’s first bog-inflected exhibition, entitled Ground and Unground, and accelerates an organic enterprise that summons the tropes and terminology of prehistoric mires more frequently associated with the ancient peat morasses of Scandinavia and Ireland. In truth, however, the motif of time’s slow reinvention of cultural artifacts, its gradual remodeling not only of an object’s surface, but of a viewer’s maturing relationship with it, can be traced back to the late 1990s and Alexander’s earliest works.

Ozymandias (1998-9), for example, whose formidable canvas rises to over eight feet in height, traces in painstaking detail the snow-shattered visage and rain-sculpted torso of a saint’s statue that stands in a quadrangle in Oxford University, where Alexander attended the Ruskin School of Art between 1993 and 1995. Ozymandias disorientatingly takes as its title a name that is more frequently associated with the British Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, and his famous sonnet published in 1818 about a destroyed sculpture of the ancient Egyptian pharaoh Ramses II (who reigned in the thirteenth century BC). The anachronism is a deliberate gesture intended to help viewers unlock the meaning of Alexander’s larger endeavor: the accelerated eroding of art and time to an eternal present in which all works are contemporaneous—equally imposing and impressionable, equally resonant with longing and longevity, defiance and desire. Time’s devolutionary disfigurement of the sculpted saint’s weather-beaten face returns its dogmatic, ecclesiastical stare to the gawp of prehistorical stoniness: the long lithe line that sealed the lips has slowly weathered wide; a sense of sway down robe-hung hips has smoothed into his side,

swimming beneath a million skies— estranged, amphibian— til all is changed, even the eyes back into God again.

from ‘Conversion: The Ruined Statue of a Saint’ (2004), lines written after Mark Alexander’s Ozymandias11

A central theme of Alexander’s work, history’s relentless erosion of an object’s aesthetic contours, assumes tragic significance in an ensuing sequence of paintings (executed some six years after Ozymandias)—a series which finds the artist experimenting for the first time with the metamorphosis of canonical works from the history of art that have drifted to the forefront of cultural consciousness. The eight canvases that comprise The Blacker Gachet (2005-6), arguably Mark Alexander’s best-known works, recast Vincent Van Gogh’s affecting portrait of his physician, Dr. Paul-Ferdinand Gachet (who treated the Post-Impressionist in the last tragic weeks of his life), by vacuuming from the melancholic canvas every last vestige of discernable light, as though the sitter were gazing from the undrudgeable depths of an emotional or existential abyss. Inspired, on one level, by the actual disappearance of Van Gogh’s original painting (not seen in public since its owner, who died in 1996, threatened to be cremated with the portrait), The Blacker Gachet gives visual voice to the unavoidable oblivion to which all things materially tend, while investing loss itself with the fructifying virtue of dark fertile ground. In the impasto’d emptiness of The Blacker Gachet, which fastidiously echoes every brushstroke of the 1890 portrait, historical bereavement for what has passed on the one hand and a foreshadow of a work’s mystical regeneration on the other—the seer and the seen—collide to create a countenance of bold fragility.

The merging of past and present—the looking and the looked at—is intensely achieved in Alexander’s subsequent series invoking the romance of antique weaponry. Shield (2008) sees Alexander fashioning on large round canvases of different monochrome colours—bronze, silver, cerulean, carmine, and gold—mind-forged replicas of classical military protection. Surfacing to the centre of each aegis is a portrait of the artist as a small child, reconstructed from an old black-and-white photograph, his cheeks billowed, puffed to popping point, as if on the verge of sounding from between bugle-puckered lips the last dirge of a battle-wearied world. Critics commenting upon the series compared the apocalyptic purse of the infant artist’s mouth with the desperate gasp of a drowning boy, as though Alexander’s childhood countenance were slowly slipping beneath the annihilating surface of this, the world’s last work of art. The ambiguous, suspended sense of submersion and emergence, of drowning and rebirth, anticipates the ambivalent preoccupations of American Bog—its simultaneous acknowledgement of a symbol’s decay and endurance, demise and resurgence.

When the seven canvases of Shield were first exhibited, the floor of the gallery space into which they unsettlingly stared was strewn with the rusted weight of five huge corten steel rings—heavy hollow hubs whose sensuous design of smooth, sloping concentered lips was based on ancient Minoan ceramics. The spinning patina of the empty discs, whose sprawling scale and sense of eternal abandonment recall the durable austerity of a Richard Serra sculpture, was formative to the artist’s emerging fascination with the inexorable alchemy of natural forces—organic processes that at once augment and erode the careful handiwork of even the most history-conscious sculptor.

The unveiling of the paintings that comprise Shield and its accompanying rings in 2009 coincided with the artist’s return to the reinvention of art historical icons, and in particular the works of Netherlandish masters Van Gogh and Hieronymus Bosch. For a sequence of some thirteen paintings entitled Via Negativa (2008-9), Alexander isolates a mournful music from the familiar notes of the Dutch artist’s famous series of sunflower canvases, executed in Arles in 1888. The effect is achieved by courageously draining the well-known works of the very element for which they are most adored—the vibrancy of golds and burnt yellows that bleeds from every pore of petal, vase, tabletop, and wall in Van Gogh’s originals. In so doing, Alexander sculpts a charred vision of animated works that have, in the century since their initial conception, continued gradually to decay in the humid hothouse of history, as though wearied by intervening world wars, ethnic cleansings, and the rise of terror. Every brushstroke of Alexander’s unnerving screen-prints chronicle the ceaseless suffering of a traumatized world as the bouquet’s dark seeds ooze, weeping down the decomposing canvas.

The notion of uncannily living works whose subjects mystically age over time, like Oscar Wilde’s portrait of Dorian Grey, is taken to at once dizzying and disquieting extremes in a subsequent work, All Watched Over By Machines of Infinite Loving Grace (2011). Here, the artist revivifies Bosch’s triptych from the turn of the sixteenth century, The Garden of Early Delights, by subtly geriatrifying figures in it, finely fatiguing not the surface of the work (in the manner of forgers who artificially age counterfeit canvases), but the supple complexions and fragile physiques of the characters that Bosch depicted in his Medieval masterpiece—as though the spiritual garden were a place, not of organic regrowth, but of infinite decomposition and demise. With Via Negativa and All Watched Over By Machines of Infinite Loving Grace, works in which art mystically distends its existence beyond the ostensible limitations of time, Alexander prepares the soil for the discovery of a deeper space of greater aesthetic complexity still, one in which decay and regeneration are not sequential but synonymized, and become one and the same.

So we arrive, inevitably, at the bog. The first wave of paintings inspired by the curative tannins that moil mysteriously within these natural mires—acidic salves capable of transforming the fibers of perishable flesh into durable, time-defying objects of wrinkled magnificence—Ground and Unground fossicks from popular consciousness a series of well-known works: from Albrecht Durer’s Praying Hands (c. 1508) to Paul Cezanne’s The Boy in The Red Vest (c. 1888-90), from Caravaggio’s Narcissus (1597-99) to Jean-Francois Millet The Sower (1850). The sequence, unveiled in 2012, marked a significant shift in the texture of the artist’s work, as the paintings exude the leathery, rumpled feel of slowly petrified tissue, the oily gleen of turf-marinated muscle. Where the power of Alexander’s earlier works depend on the painstaking reconstruction of every brushstroke of the original, the new works appear gestureless, unpainted—the product of excruciating subterranean pressure and fertilization rather than the tutored toil of the artist’s wrist.

On its surface, it would be easy to locate Alexander’s work within the trend of Appropriation Art—to compare his efforts with those of collagists who rely on allusion to well-known images in the creation of their works. The reality is otherwise. Where Appropriation Art quotes an earlier object, the paintings excavated from the bog of Alexander’s imagination are the antecedent work incubated in the soulful, accelerated medium of suffering and time. The canvases that comprise Ground and Unground, and anticipate American Bog, are not intended merely to recall the idea of prior works but to rejuvenate them. It would be more appropriate, as it were, to assert that Alexander’s work exemplifies what might be called Incorporation Art, where “incorporation” reaches back to the Late Latin verb incorporare, meaning “to join into a single body”. The canvases of Ground and Unground represent, in a sense, a realization of possibilities provided for in the very DNA of the original works, and their eventual articulation by Alexander conjugates implications in the initial paintings that were always present, but never enunciated. Alexander’s bog paintings do not seek to comment upon works from the past, but to revive them and “to join” them in “a single body” of endless regenerative decay and rebirth.

Where many of the works collected into Ground and Unground are unified thematically by modalities of the garden—by the recurrence of tilled, opened, or rain-soused ground—those that gather under the rubric of American Bog share an arguably more urgent quality: the cultural fatigue of overexposure that has slowly sapped the meanings with which they once powerfully vibrated. Embarked upon at an historical moment when the United States struggles to maintain the traction of social and economic recovery, following years of soul-wrenching wars abroad and recessionary fears at home, American Bog forges a new symbological glossary, rescuing from the mire icons whose inner music has been so overplayed we no longer can hear it.

More Mark Alexander Articles

Reflections on the Shield of Achilles