The Shield of Achilles - Mark Alexander

Reflections on The Shield of Achilles by Andrew Graham-Dixon

In the annals of mythology and history, few artifacts captivate the imagination like the weapons and armaments of legendary heroes. From the swords of valiant knights to the shields of ancient warriors, these items often bear tales of valor, tragedy, and intricate symbolism. One such notable piece is the Shield of Achilles. While this piece will touch upon its significance, it also delves deeper into related tales, particularly the story of the gilded boy and the evolution of shields from practical defense mechanisms to powerful symbols of status and artistry.

Origins and Symbolism: The Gilded Boy's Tale

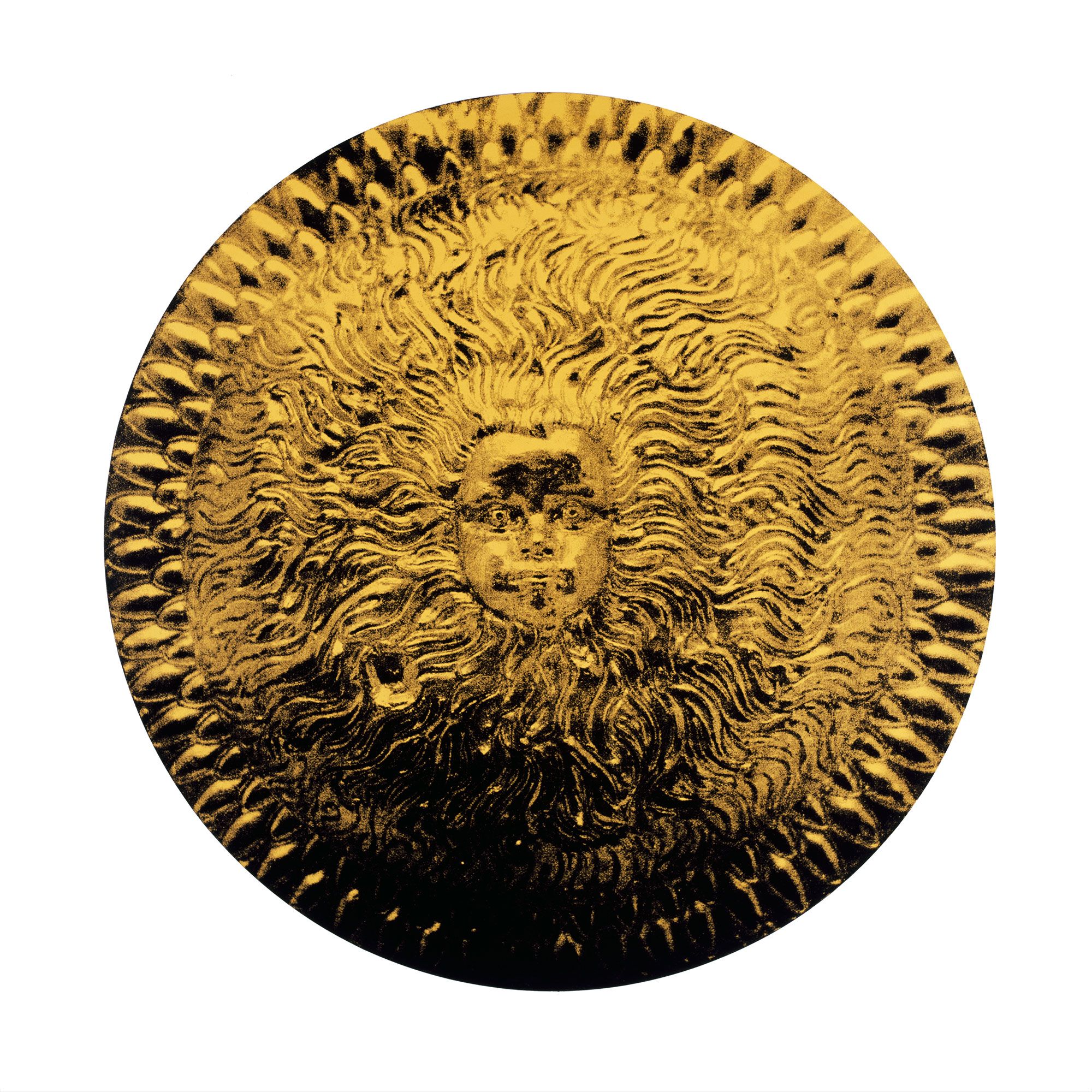

The startled boy is fixed in a circle of gold. He has a shock of hair like a lion’s mane. He thought he was a lion, king of his world. He thought he was lord of all. But he was wrong. Now there is outrage in his eyes.

The undulant coils of hair encircling his face might actually be waves of water. He looks appalled, horribly breathless, like someone on the point of asphyxiation. He could be a drowner coming up for air, or sinking into unplumbed depths.

The gilded boy also resembles a seraph: blessed head without a body. His cheeks are puffed out, like the cheeks of a seraph. But he has no angel’s trumpet to blow, no place in the heavenly host.

He is a face on a shield.

The Epic Tale of Achilles' Shield: Craftsmanship, Symbolism, and Fate

This is a story of shields. It begins in ancient Greece.

Hephaestos, god of fire and forging, created a shield for Achilles to protect him during the Trojan Wars. Homer describes what Hephaestos wrought, in Book 18 of The Iliad:

“He threw unwearying bronze on the fire, and tin, and precious gold and silver: then he set the great anvil on the anvil-block, and gripped a mighty hammer in one hand and fire-tongs in the other…

“The body of the shield was made in five layers; and on its face he elaborated many designs in the cunning of his craft.

“On it he made the earth, and sky, and sea, the weariless sun and the moon waxing full, and all the constellations that crown the heavens…

“And on it he made two fine cities of mortal men…

“And on it he made a field of soft fallow, rich ploughland, broad and triple-tilled…

“And he made on it a vineyard heavy with grapes, a beautiful thing made in gold…

“And the famous lame god elaborated a dancing-floor on it, like the dancing floor which once Daidalos built in the broad space of Knosos for lovely-haired Ariadne…

“And he made on it the mighty river of Ocean, running on the rim round the edge of the strong-built shield…”

Men and women courted one another on the shield of Achilles. Bold warriors contended with one another, in its five-layered fields of finely wrought metal. Innocent shepherds tended their flocks and played music to one another, only to be suddenly overwhelmed and killed by soldiers. The shield was like the world itself, an amalgam of beauty and love and death.

Achilles was almost, but not quite, immortal. His mother, Thetis, had dipped him in the river Styx when he was a child. Every part of his body had been rendered invulnerable by the sacred waters – every part, save the ankle by which she held him. His death came to pass when he was mortally wounded in the heel by an arrow from the bow of Paris. The shield of Achilles was magnificent but it could not save him from the death that was destined for him.

Modern Reflections: Auden's Reimagining of Achilles' Shield

What might a modern shield of Achilles look like? In 1953, W.H. Auden wrote a poem inspired by the legend of the shield. He was not only thinking of Homer, however. He also had the horrors of the Second World War in mind. In Auden’s version of the myth the Achaean world of Homer has been so darkened, so polluted by modern atrocity, that Hephaestos cannot bring himself to fashion images of beauty any more. The modern soldier, this new Achilles, cruel and terrible, has no capacity for love, and no openness to light and loveliness. The images on his shield mirror his moral emptiness, and the wasteland of a world through which he moves. In the poem, Auden imagines the mother of Achilles, Thetis, watching Hephaestos as he works:

“She looked over his shoulder For athletes at their games, Men and women in a dance Moving their sweet limbs Quick, quick to music, But there on the shining shield His hands had set no dancing-floor But a weed-choked field.

A ragged urchin, aimless and alone, Loitered about that vacancy, a bird Flew up to safety from his well-aimed stone: That girls are raped, that two boys knife a third, Were axioms to him, who’d never heard Of any world where promises were kept, Or one could weep because another wept.

The thin-lipped armourer, Hephaestos hobbled away, Thetis of the shining breasts Cried out in dismay At what the god had wrought To please her son, the strong Iron-hearted man-slaying Achilles Who would not live long.”

Renaissance Shields: From Pomp to Power Symbolism

During the Renaissance, the beautifully wrought shield had become one of the most potent symbols of a ruler’s might. Throughout the 1540s and 1550s, court armourers across Europe competed with one another to fashion splendid parade shields for Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor. Such objects could serve no practical purpose in battle. They were far too heavy and ornate for that. They were objects of display, flaunts of pomp and magnificence. They were proclamations of a pride so great it might be taken for the delusion of omnipotence. Such objects mark that moment in the history of western civilisation when the shield truly mutated into a work of art.

Charles V and the Artistry of Dominance

There is a fine example in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York. It was created for Charles V by his Milanese armourers in about 1555, to commemorate the Battle of Muhlberg. During the battle, Charles had defeated and humiliated his greatest rival, the Elector of Saxony. The moment of surrender is memorialised in the intricate bas-relief that occupies most of the shield. Charles and his generals sit astride their horses as their vanquished foe kneels to acknowledge their supremacy. The scene of war is also a scene of natural beauty, a landscape in which hardy oaks thrive. Distant hills and mountains form a jagged horizon. The shield is also, implicitly, a kind of map. It shows new territory conquered.

The Muhlberg shield was consciously intended as a Renaissance version of the shield of Achilles, the literal revival of a fabled object from antiquity. The men who made it certainly had the legend of Hephaestos, and of a shield that might evoke an entire landscape, in their minds. But there was another classical legend that would also inspire armourers – and artists – to create shields for the powerful. It was the legend of Perseus and Medusa, the monstrous Gorgon.

The Medusa Shield: Myth, Might, and Monarchy

In Greek myth, the serpent-haired Medusa turned all who looked upon her to stone, until the hero Perseus, looking only at her reflection in his brightly polished shield – the warrior’s equivalent of a driver’s rear-view mirror – cut off her head with his sword. During the age of the Renaissance and the Baroque, the so-called “Medusa shield”, a shield actually embossed with the image of the Medusa’s head, became popular among rulers who wished to cultivate an aura of heroic invincibility. Charles V had more than one parade shield decorated with the image of the Medusa’s snake-haired head. Several were fashioned for him by the armourer Filippo Negroli, and his workshop.

To carry a shield embellished with the Gorgon’s staring face was implicitly to claim the monster-slaying powers of Perseus himself. Other layers of political symbolism were involved. The modern ruler’s myth of himself as Perseus carried an implicit warning for his people. They were to obey his commands, or else. Monstrous disobedience would be punished, just as the monstrous Gorgon had once been slain. When Benvenuto Cellini’s great statue of Perseus with the Head of Medusa was set up by Cosimo I, the Medici ruler of the Florentine state, in the heart of Florence itself, its message was unambiguous. Florence was no longer a republic, the statue declared, but a dictatorship. Any dissent would be ruthlessly punished. The sculpture was created between 1545 and 1553. Cellini’s sculpture took the message of “the Medusa shield” and made a grand public statement of it. The head of the Medusa is brandished, by Perseus, like a threat. It is a vivid demonstration of what would happen to anyone with the temerity to resist Medici rule.

Art's Intersection with Myth: The Evolution of the "Medusa Shield" in Painting

The “Medusa shield” would have another life too, in the form of painting. Giorgio Vasari tells us that Leonardo da Vinci was the first artist to conceive a picture in the form of a shield, and that his inspiration was the Perseus legend. In Vasari’s telling of the story, Leonardo took a shield of fig wood:

Leonardo's Vision: Breathing Fear into Art

“And after he had covered it with gesso and prepared it in his own manner, he he began to think about what he could paint on it that would terrify anyone who encountered it and produce the same effect as the head of the Medusa. Thus, for this purpose, Leonardo carried into a room of his own, which no one but he himself entered, crawling reptiles, green lizards, crickets, snakes, butterflies, locusts, bats, and other strange species of this kind, and by adapting various parts of this multitude, he created a most horrible and frightening monster with poisonous breath that set the air on fire. And he depicted the monster emerging from a dark and broken rock, spewing forth poison from its open mouth, fire from its eyes, and smoke from its nostrils so strangely that it seemed a monstrous and dreadful thing indeed…”

Leonardo’s wondrous shield is lost, but another painted “Medusa shield” does survive. It was created at the very end of the sixteenth century, by Caravaggio. Like Cellini’s statue of Perseus with the Head of the Medusa, it was presented to a Medici ruler.

Caravaggio's Interpretation: A Mirror of Death and Power

Caravaggio’s biographer, Giovanni Baglione, records that the artist created “a head of the terrifying Medusa with vipers for hair placed on a shield … sent as a gift to Ferdinando, Grand Duke of Tuscany.” Created in 1598, it is one of Caravaggio’s most startling inventions. Painted on to a circular piece of canvas stretched over a convex shield of poplar wood, the picture conjures up the legendary monster at the instant when she breathes her last. In Caravaggio’s painting, thick jets of blood spurt from the horrible creature’s neck, which has been neatly severed just below the jaw. Her eyes stare and her mouth opens in a soundless scream. The snakes of her hair coil convulsively, each writhing in its own separate corkscrew agony of death.

Leonardo had painted a picture of the Medusa that seemed wittily appropriate as the decoration of a shield. Caravaggio did something bolder and conceptually far more pure. He created a painting that sought to transcend painting and become the very thing that it depicts. His Medusa is not a painting of a shield, or at least it pretends not to be. It pretends to be the shield itself, held in Perseus’s hand at the very instant when he has killed the Medusa. To look at the picture is to become the conquering hero himself – to gaze, through his eyes, at the reflection of the Medusa, as she in turn watches herself die, in her own reflection, in the shield’s mirror.

Caravaggio’s Medusa transforms whoever holds it into Perseus himself. To give such a picture to a Medici was to flatter him in a comfortingly familiar way. But there is a subtle, slightly bitter taste to the compliment. The image of Medici power is also an artist’s vision of what that power might one day do to him. He modelled the Medusa on his own features. The dying face, frozen on the shield, is the painter’s own face.

From Masks to Sunflowers: The Baroque Era's Symbolism and the Artistic Evolution

The shield, as a symbol of Baroque power, was closely allied to the mask – which makes of the face itself a kind of shield, impervious to the inquisitive gaze.

The Royal Masquerade: Masks as Shields of Godhood

During court pageants, Louis XIV, “the sun King”, sometimes wore a mask that made his face into an image of the radiant sun, a wheel spiked with rays of radiance. During masqued entertainments at Versailles he took on the role of Apollo, the sun god. Around him his courtiers literally revolved, like planets turning around the centre of the solar system.

The Gilded Illusion: Monarchs, Myth, and Immortality

Vestiges of such symbolism – the symbolism of an absolute, god-like power – can be found in the objects created for many other European rulers. The Rustkammer of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen in Dresden contains a remarkable selection of masque accoutrements created for Augustus the Strong of Poland, during the early eighteenth century, by the goldsmith and metalworker Johann Melchior Dinglinger. They include a pair of caparison ornaments forged in the shape of startled golden suns, worn by Augustus’s horse on the occasion of a particularly grand court entertainment (“the Entry of the Gods and Night-time Running at the Ring in Dresden”, in 1709). Even more spectacular is the so-called “Sun-Mask” of Augustus, created from embossed and gilded copper. It is a mask of golden metal, beaten almost as thin as paper, perfectly moulded to the ruler’s face.

The Baroque ruler is gilded by the myth of his permanency. He believes that he is immortal, a second sun placed in the firmament by God himself. According to the divine right of kings, he is indeed himself another God. “You are a little God to sit on his throne and rule over other men,” James I told his son, Charles I, whose tragedy it would be to believe in his own myth all too completely.

Sunflowers as Symbols: Loyalty, Faith, and Transience

Intertwined with these images of masqued gods and suns is the image of the sunflower. Because the sunflower follows the sun through its arc across the sky, always facing towards it, it became identified both with religious faith and with political loyalty. To follow the sun is to follow God. It is also to follow his representative on earth, the “little God”, the king. So it is that Charles I’s court painter, Anthony Van Dyck, depicted himself with a sunflower as his attribute. Around the painter’s slim neck is a golden chain, given to him by the King of England. The chain completes the chain of meanings. Van Dyck meant his picture as a gesture of gratitude and as an oath of fealty. He believed in his king, as he believed in God. But the sky is full of fast-moving clouds. There is a melancholy conscience of transience in the painter’s eyes, the knowledge that nothing, however apparently fixed and certain, will last forever.

Van Gogh's Sunflowers: A Dual Tale of Hope and Despair

The history of art is the history of disillusionment. With the sunflower, Vincent Van Gogh completes the process. Painting in an age that no longer believed in kings and that struggled to believe in God, he made the sunflower the emblem of his own deepest desire – the desire to be able to believe in God and good and the bright dream of a life lived, among the blessed, forever. Van Gogh had been a preacher, but towards the end of his short life he could only think of himself as a sunflower, always turning to the light, or trying to. But he painted dead sunflowers too, dried up and shrivelled: sunflowers unable to follow the sun.

From Immortality to Reality: The Artistic Reckoning of Self

The story of shields and gods and wanting to live forever ends with the boy fixed in the circle of gold.

He wanted immortality, he wanted to rule the world too. Art has made that possible, but in a way that never occurred to him. He is frozen in breathless bewilderment. He is the victim of his own false dream, like the old kings and their doomed legends, like Louis XIV and Augustus the Strong – like Midas turned to gold.

He is also – as the Medusa of Caravaggio – a disguised self-portrait. A photograph of the artist himself as a boy has been transmuted into this face on a shield. The self depicted is an old self, reconsidered. It is the childish, selfish self everyone, in the end, has to abandon.

The child, the egotist, the king, have this in common. They think the world revolves around them, and them alone. The boy is made to confront the falseness of this proposition in the very forms of his realisation. He is not one, but many. He is an image multiplied, in red and blue and other colours. In one of these likenesses, a pale and faded silver, the paint has run in such a way as to give him a bloodied nose.

To be alone in with these images is to be in a room full of fallen gods. Each is lost in contemplation of his own mirror-likeness, startled by the presence of another – others – just like himself.

Why did the artist create these pictures? Perhaps he did it as a way of waking himself up forever from all those old, sad, dangerous legends. A way of marking his distance from the old illusions, of moving from there to here and trying to embrace reality – whatever that may be.